Pennsylvania attorney Robert Mongeluzzi, a Saltz Mongeluzzi Bendesky founder, has been dubbed in the press as “the master of disasters.” He sends a 45-minute videotape consisting of case-specific liability and damages to the decision maker at the defendant’s insurance company.

“The decision maker is rarely in the room at a settlement conference or the mediation,” Mongeluzzi said. “They’re usually in some corporate tower in Chicago, New York or London. But the one time I know I can talk to them is when we have a settlement film.”

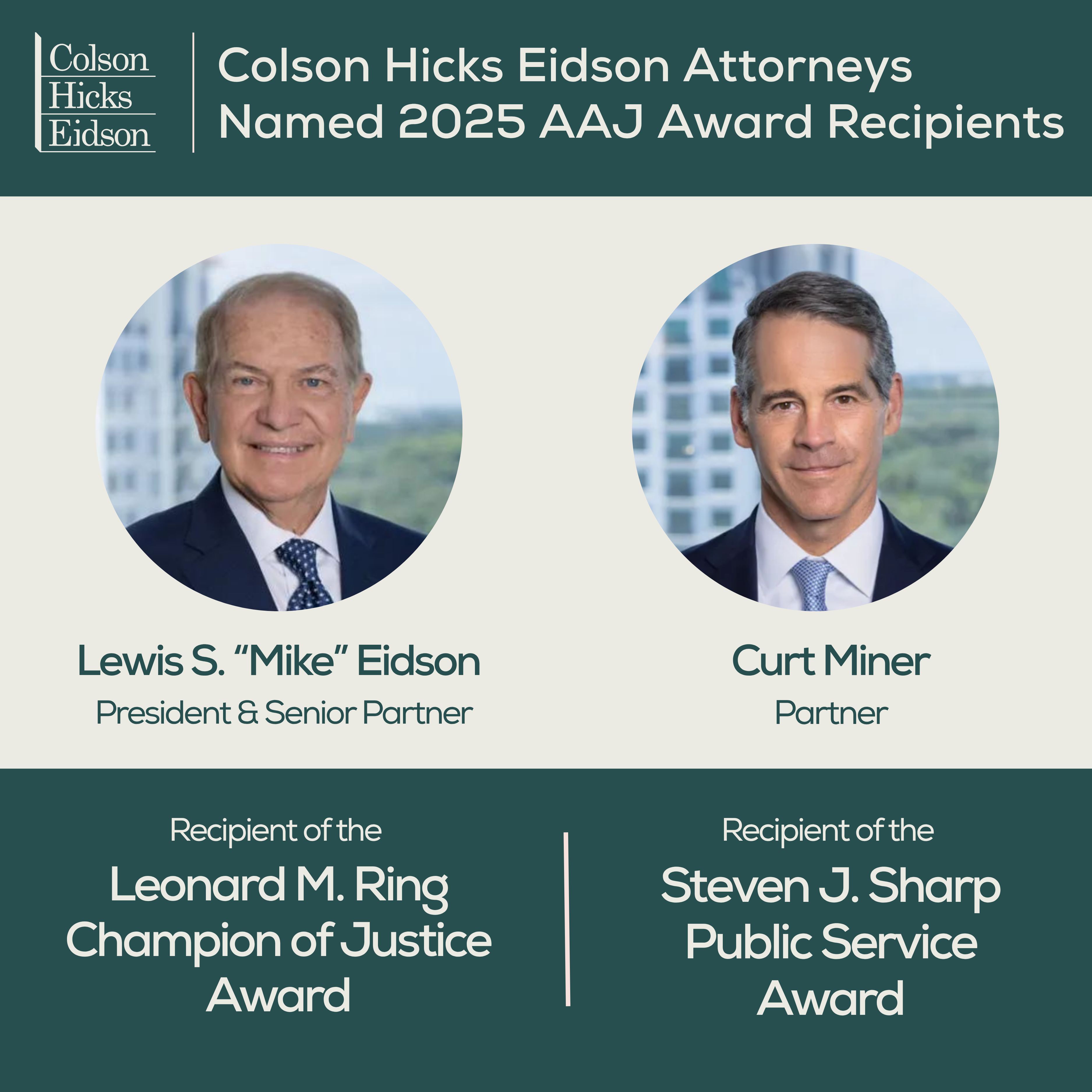

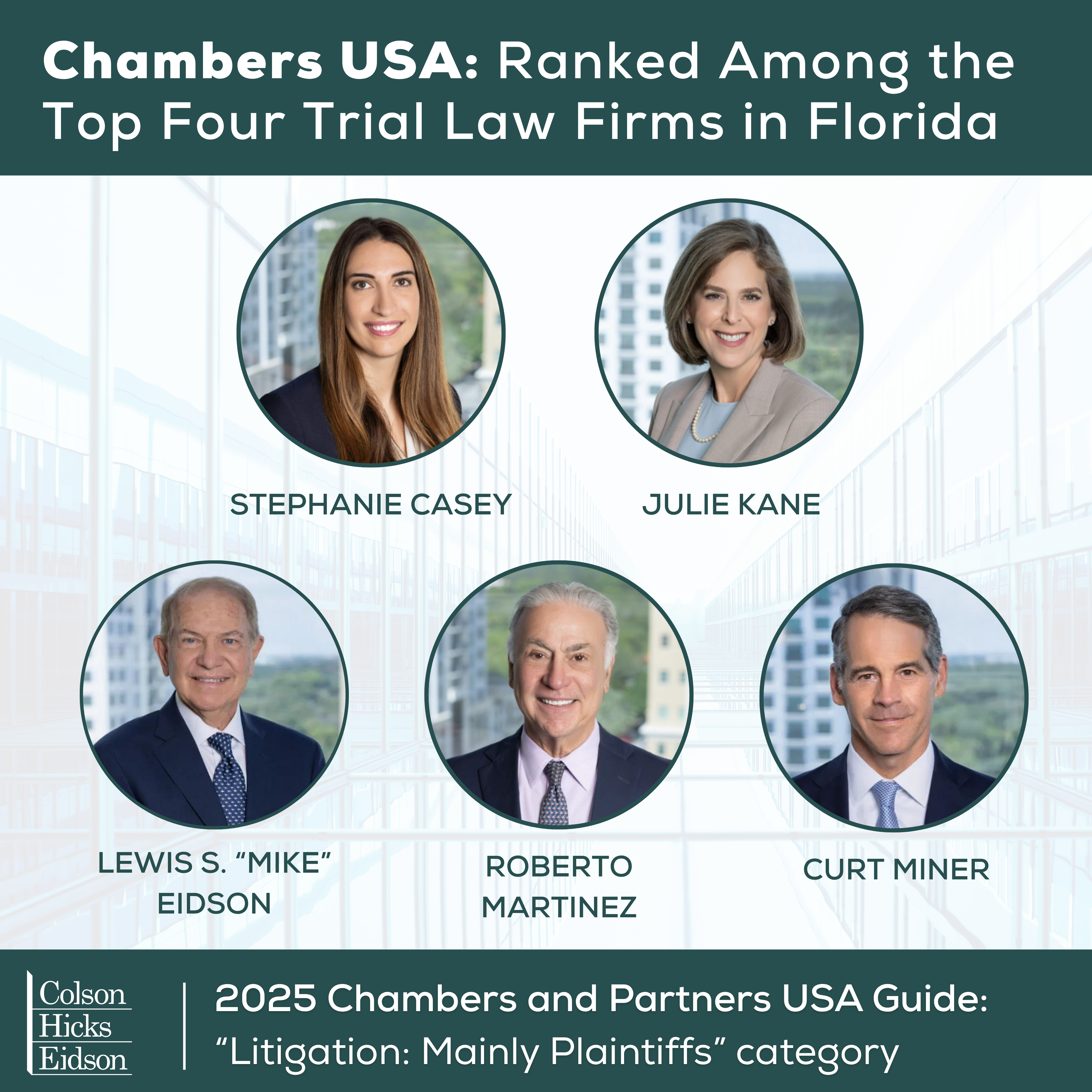

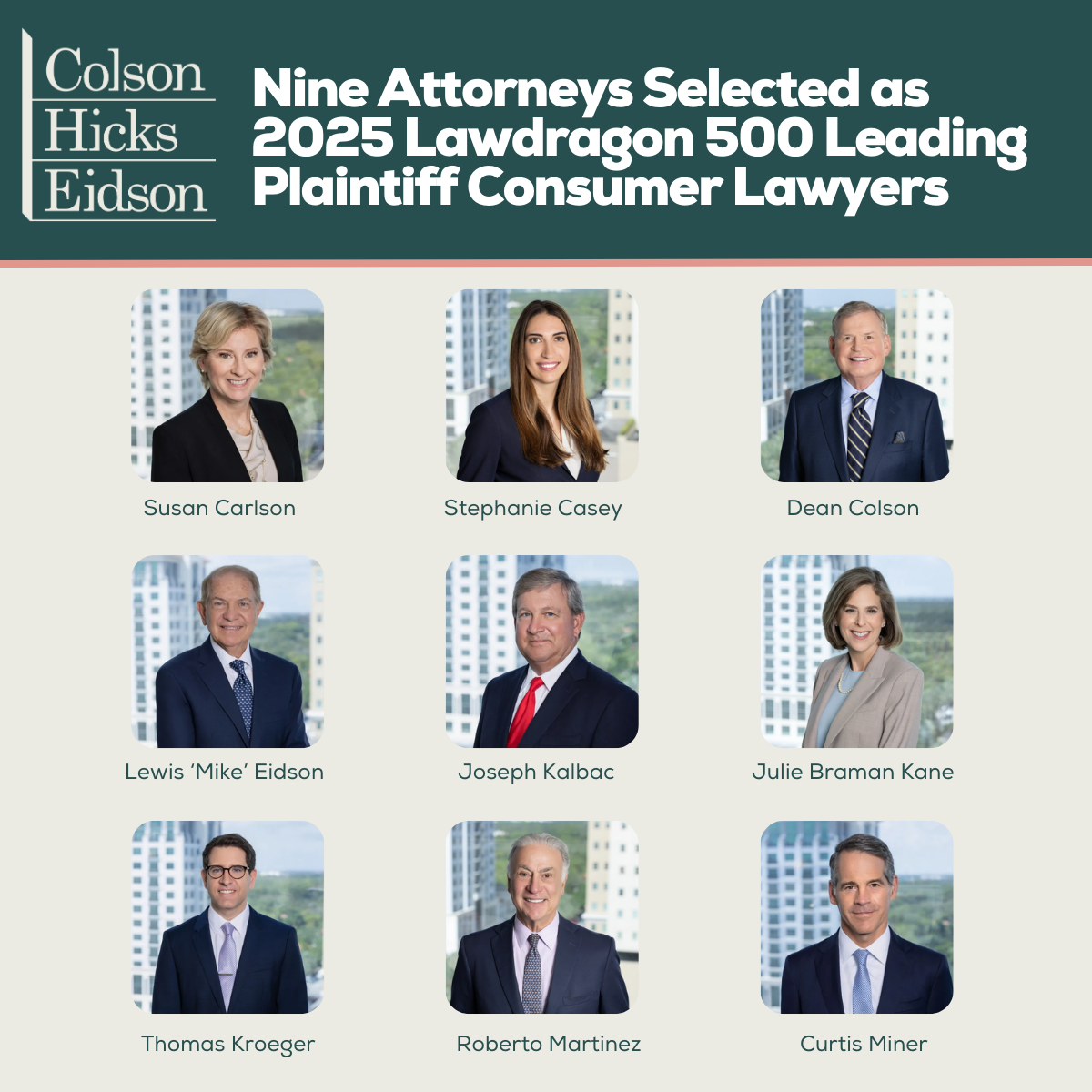

Florida attorney Curtis Mine, a Colson Hicks Eidson partner and an expert in structured settlements, said the Sunshine State “punches above its weight” in consolidating multidistrict litigation and class actions.

“The average time for completion of a civil lawsuit from filing to completion, in past years, the Southern District of Florida is ranked first or second in the country,” Miner said. “As the stakes increase, the defense strength increase.”

While both attorneys litigate differently and in different states, they both share a common thread: They routinely obtain so-called nuclear settlements and practice among the six states, including California, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

The states account for nearly 65% of the nuclear verdicts, per a U.S. Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform report.

“Nuclear settlements are a function of nuclear verdicts, and a recognition that going to trial is a risky proposition—both before and now,” said Lee Teichner, a partner at the Am Law 100 firm Holland & Knight.

Nuclear settlements, according to Robert Tyson, managing partner at Tyson & Mendes in San Diego, California, are either more than $10 million or are settlements in which non-economic damages, like pain and suffering, greatly exceed economic damages, such as medical bills.

Tyson explained to defense lawyers how to avoid runaway jury verdicts in his book, “Nuclear Verdicts: Defending Justice for All.”

This year, Tyson plans to publish a sequel with a more data-driven approach to the subject. Tyson has also developed software that uses artificial intelligence to advise insurance companies which of their cases is likely to end in nuclear verdicts.

Focus on Federal Appellate Courts

Thomas R. Kline, a founding partner of Kline & Specter in Pennsylvania, has taught at several law schools, including the Drexel University Thomas Kline School of Law. Kline routinely obtains these nuclear settlements, but objects to the name as a defense bar tactic.

Kline said there are restrictions placed in various states, which prevent jurors from returning eight-figure verdicts, which in turn prevents the lawyers from obtaining an eight-figure settlement. It is an example of the effort by insurance companies or governmental entities to restrict the damages that can be claimed and recovered.

“There’s a ‘Look what Texas is doing’ and then they try to do that in another state,” Kline said. “But each of these settlements are driven by the law in the state in which it is drawn. You can only change it in two ways: convince the highest appeals court or the legislature to change the law.”

And the stakes are high, as Miner of Colson Hicks said that future rulings by the federal appellate courts could change whether nuclear settlements continue to thrive in those six states in which nuclear verdicts abound.

Miner pointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit—an outlier—which entered a ruling last week on what class representative incentive awards are allowed.

The Eleventh Circuit reversed a nearly $10 million settlement over the brain performance supplement Neuriva after finding a class member had standing to object.

The Eleventh Circuit ruling affirmed the precedent set in Johnson v. NPAS Solutions.

The appellate court held that incentive awards for class action representatives that compensate them for their time and reward them for bringing lawsuits are prohibited.

Miner cited the recent trend of success in appeals of settlements based on standing as an example of what could drive defense reform if the concept spreads outside of the Eleventh Circuit.

The result could affect where nuclear verdicts are heard and thereby, without the threat of trial, alter the jurisdiction in which attorneys obtain nuclear settlements.

“The ruling could disincentivize potential victims of consumer fraud or consumer deceptive conduct, participating in class actions,” Miner said. “They may just say, ‘Well, I just don’t want to have to put in that kind of time to do it if there’s nothing for it.”